ISSN electrónico: 2172-9077

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14201/fjc2020211326

HOPE AND INEVITABILITY IN 13 REASONS WHY. A COMPARATIVE DISCOURSE ANALYSIS OF THE SERIES’ FIRST SEASON AND IT’S BEYOND THE REASONS DOCUMENTARY COUNTERPART

Esperanza e Inevitabilidad en Por 13 Razones. Un análisis de discurso comparado entre las primeras temporadas de la Serie y del documental Beyond the Reasons

Dr. Roberto GELADO-MARCOS

Profesor Adjunto en Universidad CEU San Pablo, España

E-mail: roberto.geladomarcos@ceu.es

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4387-5347

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4387-5347

Santana Lois POCH-BUTLER

The Open University, Reino Unido

E-mail: santanalpb@gmail.com

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2590-7795

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2590-7795

Dr. Plácido MORENO FELICES

Profesor Colaborador Honorario en Universidad CEU San Pablo, España

E-mail: placido.morenofelices@colaborador.ceu.es

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0912-2763

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0912-2763

Fecha de recepción del artículo: 18/07/2020

Fecha de aceptación definitiva: 15/10/2020

Abstract

The release of 13 Reasons Why in March 2017 attracted not only audiences worldwide, but also a considerable amount of academic attention. A good share of the academic production on the series, though, has focused mostly on its effects. For this reason, and in an attempt to approach the debate from complementary angles, this paper aims at examining the motivations expressed by those involved in the creative process of the show and comparing them with the actual discourse in the series’ first season. In order to do that, the methodology triangulates between quantitative and qualitative techniques to approach the research problem from equally complementary angles. The results of these analyses confirm that the creators’ motivation goes beyond mere entertainment, but also that inconsistencies between the discourses in Beyond the Reasons and 13 Reasons Why’s first season have been found.

Key words: TV; Teen Series; Suicide; Communicator’s Responsibility; Adolescents.

RESUMEN

Cuando, en marzo de 2017, Netflix lanzó Por 13 razones, la serie no solo cautivó a una audiencia planetaria, sino también a un buen número de académicos interesados por el fenómeno televisivo en sí. Una buena parte de la producción académica relacionada con la serie se ha centrado desde entonces, sobre todo, en el estudio de sus efectos. Por esta razón, en un intento por abordar el debate desde ópticas complementarias, el presente artículo aspira a examinar de modo comparativo las motivaciones expresadas por los creadores de la serie y el discurso mismo de la primera temporada de la serie. A tal fin, la metodología triangula entre técnicas cuantitativas y cualitativas que abordan el problema de investigación desde ángulos complementarios. Los resultados del análisis confirman, por un lado, que las motivaciones de los creadores trascendían el mero propósito de entretener y, por otro, que los discursos de Por 13 razones y Más allá de las razones, el documental tomado como referencia para examinar las motivaciones de los creadores de la serie, presentan inconsistencias significativas.

Palabras clave: Televisión; Series de adolescentes; Suicidio; Responsabilidad Social del Comunicador; Adolescentes.

1. Introduction

Even though Netflix has historically seemed reluctant to publicise audience data of specific items in its catalogue, some less specific have started to hint at clues on the popularity of its TV series. In a press release issued at the end of 2017, the network published several rankings with top shows regarding different categories, amongst which one of them distantly resembled audience ratings: Netflix listed the ten top shows that had been watched more than two hours per day throughout that year. 13 Reasons Why (Brian Yorkey, 2017-20) ranked third in the list. This could be considered a first token of its impact, though it is definitely not the only one: the show’s first season was not only attractive for audiences worldwide, but also for a significant amount of academics around the world, as will be discussed in more detail in the next epigraph.

2. State of the Art

Since its release in March 2017, Netflix original show 13 Reasons Why attracted a considerable amount of academic attention. It is no surprise that, youth suicide being its (main) topic, most of these works focused on the impact the show may have on, especially, vulnerable audiences. Mueller (2019, p. 499) recalls, in this respect, that «though popular, the show is also quite controversial. Scholars were quick to raise concerns that the show may encourage suicide as an option, particularly for vulnerable audience members (e.g., American Association of Suicidology, 2017)», which Arendt et al. (2019) irremediably connect to the so-called Werther effect1.

Bridge et al.’s recent investigation seems to confirm this extent, with findings that indicate «a significant increase in suicide rates among US children and adolescents in the month after the release of 13 Reasons Why» (Bridge et al., 2020, p. 242). Similarly, and more specifically, Da Rosa et al. (2019 p. 4) reported that «more individuals with previous suicidal ideation, self-harm behaviour, or history of suicidal attempt reported a worsening in mood after watching the series».

This inevitable push of 13 Reasons Why–related research towards the study of effects is not new when it comes to depicting suicide (though, strictly speaking, 13 Reasons Why in general, and its first season in particular, cover more topics than just suicide): «such harmful effects have been revealed for news (Stack, 2005; Sisask & Varnik, 2012) and fictional entertainment (Niederkrotenthaler and Stack, 2017)2», though recent research also recounts that «news reporting on suicide, for example, by publishing stories about individuals who successfully overcame a suicidal crisis, can reduce suicidal behaviour—a phenomenon called the Papageno effect (Niederkrotenthaler et al., 2010)» (Arendt et al., 2019, p. 489).

In her overview of previous investigations around the 13 Reasons Why phenomenon, Mueller (2009, p. 500) insists that most of them are limited «to make causal claims about the role of media in suicide deaths and undermines our ability to be confident that 13RW is harmful for youth», due to the generalised lack of empirical data (which is precisely why she praises Arendt et al.’s study). Admitting this, she gathers significant data from Ayers et al. (2017), who discovered that the amount of individuals that searched «how to commit suicide» on the Internet increased notably after the show’s first season was released, though she also adds that searches for «suicide hotline number» also went on the rise, which may hint that «13RW may have increased distress among some viewers, but perhaps also increased help-seeking, at least for a time» (Mueller, 2009, p. 500). Data from Atarama-Rojas & Requena Zapata’s (2018, p. 210) exploratory analysis seem to confirm that the series stirred up discussion, at least, among its viewers.

Other studies mentioned by Mueller herself back up both arguments: regarding the former, Cooper et al. (2018) confirmed an increased amount of admissions at a children’s hospital for cases of self-inflicted harm; and, as for the latter, Thompson et al. (2019) found out that there was a significant growth in the messages to the Crisis Text Line after the release of the first season. In a similar line, Sugg et al. (2019) ran a quasi-experimental study that highly coincided with Thompson et al.’s postulates and revealed «a significant relationship between highly publicised celebrity deaths by suicide, and media portrayals of suicide and help-seeking patterns among young people» after the release of 13 Reasons Why’s second season.

In March 2018, the Northwestern School of Communication published through its Center on Media and Human Development a global study on audience reactions to 13 Reasons Why’s 1st season. The research, led by Ellen Wartella, Alexis Lauricella and Drew P. Cingel, was widely publicised by Netflix Media Center, which praised the study’s conclusion that «71% of teens and young adults found the show relatable, and nearly three-quarters of teen and young adult viewers said the show made them feel more comfortable processing tough topics»3. A more detailed look at the study, which surveyed around 5000 respondents (half of which had watched the show) called attention to two additional facts that are worth considering. On the one hand, there was an explicit mention to the documentary Beyond the Reasons, which was a good support practice by the network, though not enough4. On the other hand, the study noted that «individual characteristics of the viewers influence their responses to the show».

Arendt et al. (2019, p. 498) agree that «apparently, there is no one-size-fits-all solution to suicide prevention in fictional suicide depictions. It appears that audiences relate differently to such content depending on their backgrounds and viewing patterns». However, they do reach some interesting conclusions related to these aforesaid viewing patterns; notably that «those who watched the entire second season exhibited less suicide risk than those who only watched some of it, and that students were at higher suicide risk than non-students» (Arendt et al. 2019, p. 496). However, or precisely because of this widely branched -and not always easy to read- casuistry, the authors call for an increased awareness of «of the potential effects of their shows, particularly on vulnerable audiences» by media producers of suicide-related fictional content.

All these studies confirm, though, that 13 Reasons Why has attracted researching attention mostly on the side of effects -not so much on the production of content itself. It is not surprising, though, since the main appeal the studies of mass communication phenomena had throughout history was, precisely, assessing the impact they had on the large audiences they targeted. However, complex realities like social communication benefit from expanding its analysis to other ends of the phenomenon: in the communicative process, interpreting the sender’s intentions and the nature of the message have also attracted -secondarily, though recurrently- researchers’ interest. It is for this reason that the present investigation aims at complementing the profuse literature discussing the effects of Netflix’ 13 Reasons Why with an analytical approach to the nature of the message itself and its consonance with the motivations that inspired its creators.

3. Methodology

The present study focused on the show’s first season, since we deemed it to be not only the one that pioneered most of the aforesaid controversy, but also, from a narratological point of view, the season that most consistently tackled the reasons surrounding the suicide of an adolescent, which, in the end, was the premise of the series -and its title. As briefly announced before, the main research goals were to focus on the show’s discourse and to shed light on the motivations of its creators. This led to extend the analysis to a second text, the documentary Beyond the Reasons (also its first season), which was mentioned as part of the expanded universe of the show that aimed at explaining key topics covered in the show.

As a result of this first approach two hypotheses were formulated: on the one hand, that the communicative intentions of the creators of 13 Reasons Why transcended the mere controversy and aim at being responsible as social communicators; and, on the other, that the discourses of both 13 Reasons Why and Beyond the Reasons’ 1st seasons were not fully coincidental on issues that can be considered central to the aforesaid responsible exercise that the creators aimed at.

3.1. Design of the investigation

The analysis aimed at establishing a comparison of discourses that needed to sequence the investigation of the two researched items, 13 Reasons Why’s 1st season and it’s Beyond the Reasons counterpart. Providing that the first hypothesis delved into the senders’ motivations, it seemed smarter to start the analysis by trying to shed light on this hypothesis while, at the same time, outlining discourse patterns in the documentary that could be later compared to the discourse in the series themselves.

With this double goal in mind, the analysis of Beyond the Reasons’ first season was articulated in four stages that made the methodological proposal triangulate (Lewis-Beck et al., 2004) between quantitative and qualitative techniques to tackle the research goals from different angles, hence providing a more exhaustive analysis of a complex reality:

1st: A quantitative content analysis of the type of sources used in the documentary, their frequency, and a segmented analysis of the moments in which these sources appeared was implemented. Three categories of sources were proposed after a preliminary analysis of the material: actors, producers, and experts. The first category was the easiest to operationalise, since it included those sources who played a role in the series; thus, it was easy to associate with the name assigned to it. The second and third categories required further explanation: both producers and experts were related to the creation of the audio-visual content itself, though the former was understood to have an active part in the production of such material (from the creation of the novel that inspires the series to the executive production of the show) whereas the latter was assumed to have mostly an advisory role in the development of the TV series.

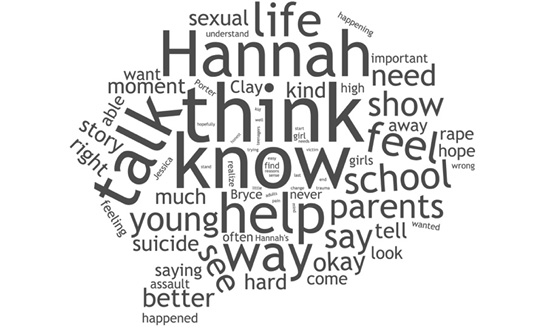

2nd: A first approach to the analysis of the actual discourse in the documentary was implemented through computer-assisted tool Wordclouds (https://www.wordclouds.com/). After the documentary was transcribed and submitted to Wordclouds, three filters were applied: firstly, only the words repeated more than four times were considered; secondly, recurring empty words detected by the tool itself were eliminated; and finally, a last filter was applied manually to additionally stop the following words: «people», «can», «just», «really», «going», «someone», «get», «one», «things», «something», «thing», «lot», «actually», «even», «will», «every», «everything», «maybe», «nothing», «first», «scene», «around», «I’m», «make», «person», «point», «sometimes», «times», «completely», «day», «episode», «especially», «guy», «happens», «Hey», «minute», «now», «put», and «time».

3rd: In order to deepen into the analysis, a second computer-assisted tool for textual analysis, MonkeyLearn’s Sentiment Analyzer (https://monkeylearn.com/sentiment-analysis-online/), was used. This tool would also serve as a quantitative passageway to a more qualitative analysis of the discourse that aimed at spotting the pattern, the tone, the topics covered, and other peculiarities of the Beyond the Reasons that could be later compared to the series’ first season.

4th: This final stage turned to the announced qualitative analysis of the documentary’s transcript in an attempt to complement the previous quantitative efforts with an in-depth analysis of aspects that may escape rigid categorisation. Discourse analysis, defined by Jones (2012, p. 2) as «the study of the ways sentences and utterances are put together to make texts and interactions and how those texts and interactions fit into our social world», seemed to perfectly match these research purposes. As Jones (2012, p. 9) himself mentions soon after this first definition, «most texts are not just trying to get only one thing done. The communicative purposes of texts are often multiple and complex», and that was precisely the scope adopted for this stage, since a documentary about a 13-episode season was indeed a complex and imbricate reality to study.

As announced before, the analysis of Beyond the Reasons was designed to set the discourse coordinates that could also be applied and discussed later on to the episodes of 13 Reasons Why’s first season in order to test the second hypothesis and determine whether the discursive patterns of the two items analysed were consonant or not.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. An analysis of Beyond the Reasons’ 1st season

The first part of the investigation focused on the analysis of the documentary Beyond the Reasons (1st season) with an aim at shedding light on both the discourse structure and peculiarities of the piece, as well as the motivations behind the production of the show it discusses. The analysis of the structure was helpful as a first token of what the creators of the series considered relevant in terms of who were recognised as validated sources to speak about the topics presented in the show, which could be later contrasted with the actual sources that were portrayed in the series themselves. Also, it would be fair to assume that whoever had a more prominent presence in the documentary could provide more accurate hints on the true motivations behind the message in 13 Reasons Why.

Tabla 1. Participants in Beyond the Reasons (1st season)

|

Actors |

Cuts (number) |

Time on screen |

|

Katherine Langford (Hannah) |

10 |

183» |

|

Alisha Boe (Jessica) |

5 |

88» |

|

Dylan Minette (Clay) |

4 |

64» |

|

Justin Prentice (Bryce) |

4 |

53» |

|

Brandon Flynn (Justin) |

3 |

37» |

|

Miles Heizer (Alex) |

2 |

36» |

|

Derek Luke (Mr. Porter) |

2 |

28» |

|

Kate Walsh (Mrs. Baker) |

2 |

14» |

|

Producers |

||

|

Brian Yorkey (executive producer) |

11 |

204» |

|

Selena Gomez (executive producer) |

4 |

47» |

|

Mandy Teefey (executive producer) |

4 |

44» |

|

Tom McCarthy (executive producer) |

3 |

54» |

|

Jay Asher (author, 13 Reasons Why) |

3 |

39» |

|

Experts |

||

|

Alexis Jones (founder of I am that Girl & ProtectHer): |

11 |

164» |

|

Dr. Helen Hsu (licensed clinical psychologist) |

10 |

147» |

|

Rebecca Hedrick (child psychiatrist, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center) |

9 |

124» |

|

Dr. Rona Hu (psychiatrist, Stanford University School of Medicine) |

7 |

99» |

Source: Own elaboration.

As explained in the methodology epigraph, content analysis was used to systematise and quantify the type of sources that were presented in the documentary. Out of the seventeen sources presented in Beyond the Reasons (1st season) there were eight actors, five producers, and four experts. A more detailed explanation of sources, positions, number of cuts and time on screen (including voice over interventions) for each one of them can be found in Table 1. This first categorization focuses exclusively on the comments of these sources on the show, so the scenes included have not being taken into account as time on screen for the different actors that appear in them.

The results of Table 1 shed some light on several aspects: Katherine Langford and Brian Yorkey are largely the most recurrently used sources in the documentary amongst actors and producers, respectively. Gaps of time on screen within the «Experts» group are not so noticeable, especially regarding the amount of participations in the documentary: whereas the actors’ number of participations ranged between 2 and 10, and the producers’ between 3 and 11, the experts’ range is more balanced (7-11). This may mean that, whereas the producers of the documentary (and, possibly, the audience) identify a «star actress» and a «star producer», there is no such thing amongst the experts –which was useful to adjust the subsequent discourse analysis.

The more balanced distribution of time on screen amongst the «Experts» group also suggested an empowered relevance of this category for the creators of Beyond the Reasons. In other words, there are fewer experts than members of any of the other groups (the number of actors that appeared in the documentary doubled the experts) but they appear more time. This possibly indicates that the producers of the documentary are aware that their targeted audience will possibly be more attracted by the faces they know from the show than any other, though they believe that it is the experts who can really provide a solid context for the discourse that they are building.

For this reason, we proposed a second layer of our quantitative content analysis that aimed at clarifying not only how much time each of the groups selected appeared in the documentary, but also when. In order to do so, the amount and duration of the interventions by actors, producers and experts were divided in three categories: a first one including the cuts within minutes 0 to 9:59, a second one from 10’ to 19:59, and a third one from minute 20’ till the end of the documentary -whose total running time was close to 30’.

Table 2. Number and duration of cuts and sources in Beyond the Reasons

|

Time |

Actors |

Producers |

Experts |

|

0’ - 9:59 |

14 (194») |

13 (181») |

7 (109») |

|

10’ – 19:59 |

11 (187») |

6 (113») |

12 (202») |

|

20’ – end |

7 (122») |

6 (94») |

18 (223») |

|

Total |

32 (503») |

25 (388») |

37 (534») |

Source: own elaboration.

The dissection by time slots confirm the suspected prevalence of experts in the overall running time of the piece studied and a content layout that places producers and, especially, actors, before experts. This could also be in relation with Arendt et al.’s (2019) findings that the show’s second season was more helpful to those vulnerable audiences who watched it entirely than to those that gave up halfway through. Applying that logic to the distribution of contents in Beyond the Reasons, and assuming that the bigger share of cuts and running time assigned to experts may reveal an implicit recognition of its special relevance, leaving these sources to the second and, mostly, third slot of the documentary may compromise its actual impact on the targeted audience.

Moving onto the textual analysis of the transcript of Beyond the Reasons, a first examination of word frequencies revealed some of the most recurring words that were later used as a start for the in-depth discourse analysis of the text. After applying the filters explained in the methodology, the resulting word cloud was completed as follows:

Image 1. Word Frequency. Beyond the Reasons’ transcript

Source: own elaboration.

The computer-assisted analysis of the transcript was completed, as noted in the methodology chapter, through the Sentiment Analyzer tool, which estimated a 55,1% predominance of negatively connotated words in the discourse utilised in the transcript of the Beyond the Reasons documentary. Computer-assisted tools were undertaken, though, as a first step to a more detailed, in-depth qualitative analysis that shed more light on the particularities of the discourse used in the documentary examined. Both served, however, as a first guide for the discourse analysis.

The systematic examination of word frequencies in the documentary studied showed, for instance, the centrality of the character of Hannah Baker, which may seem obvious providing that the premise of the show –an adolescent that committed suicide and recorded a collection of tapes explaining the reasons why she did it– focused mainly on her; but may have actually not been so clear, since the presence of other characters, especially Clay Jensen, were also quite relevant. This first textual analysis of the Beyond the Reasons transcript clarifies, though, any possible doubt: this is, above all, Hannah Baker’s show. Thus, the subsequent analysis should probably honour the centrality that the sources involved in the documentary assign to this particular character.

Three words are even more frequent than Hannah (mentioned 20 times -25 if we include the variation «Hannah’s»-) by the different sources in the documentary: know (33), think (30), and talk (30). All of them seem to point towards a recurring motivation behind the show with clear ethical implications: the sources that weave the discourse of Beyond the Reasons seem to project more ambitious aspirations than pure entertainment, namely invitations to talk and reflect about the topics covered. «Help», which ranks 5th in the word frequency list, seems to confirm the aim to transcend mere amusement and become a useful tool for the viewers.

The textual analysis also reveals recurring topics covered by the show, such as suicide (8), sexuality (8), rape (7) – and related ones, like assault (6) or victim (4)–, trauma (4), etc.; all of them related to its evident teen genre affiliation (the word «young» is repeated 11 times). Frequent mentions to other characters (though never as frequent as to Hannah) also help build the importance that the sources used in the documentary assigned to the different members of the cast: Clay (7), Bryce (6), Jessica (5), and Mr. Porter (5) lead the recurrent mentions outside of Hannah. Many of these words, even the reason why many of the aforesaid characters are mentioned so often (Bryce is the rapist, Jessica one of his victims and Mr. Porter the overwhelmed school’s counsellor that Hannah mentions as the final reason to commit suicide), may explain why the second computer-assisted tool hinted at a predominance of negative words in the transcript of Beyond the Reasons. That percentage, though, was not close to the 100% of the total discourse, which can be explained by the fact that, although smaller in proportion, inspiring and more positive words are also present in the documentary. «Hope», mentioned 7 times, or «better» (9) are a good example of such discourse trend and cross-refer again to the aforesaid intention that the different groups involved in the production of 13 Reasons Why aimed at providing their audiences something more than mere amusement.

A descent into the discursive specificities of the transcript empower this idea of hope as one of the central axes that the documentary defends the series portrait. In fact, the idea is already presented as early as in minute 1 by Jay Asher, author of the 13 Reasons Why original book, who literally states that «there’s always room for hope» and connects this conclusion to a previous thought that goes beyond the idea that talking about all the topics covered by the show is not dangerous and affirms that what is really «dangerous (is) not to talk about it». A good part of the documentary revolves around the idea of the benefits of putting the topics covered in the series in the open and the need to discuss them. At the very beginning, actor Brandon Flynn refers to 13 Reasons Why as «a story that’s going to start a conversation»; and, in a similar line, actress Kate Walsh agrees that «these are things that need to be discussed». All of that builds up a side of the discourse focused on justifying the need to talk about such topics, notably suicide -probably anticipating criticisms regarding the imitative conducts (the aforesaid Werther effect).

The suggested conversation that is aimed at may happen amongst adolescents, but also between adolescents and their parents, as stated openly by executive producer and Selena Gomez ‘mother Mandy Teefe: «Hopefully sharing these stories can help parents pay attention». The language used – that can also be visible when, in minute 4 too, executive producer and creator of the TV adaptation Brian Yorkey explains that «Adults tend to trivialize what for teenagers and young adults is not trivial teenage brains don’t work the way adult brains»– hints that the adopted point of view is predominantly the adolescents’, since parents are presented as unaware of what is going on with their kids.

Presenting the topic as something that needs to be discussed and hope as an ultimate goal of the show seems to be at the discursive core of the documentary. Executive producer Selena Gomez states at the beginning of Beyond the Reasons that they «wanted to make something that can hopefully help people because suicide should never, ever be an option» («to not seek help or end it is tragic», adds actor Dylan Minette). Digging a bit deeper, further statements by participants in the documentary show that the message of hope often collides with an idea of inevitability that, at times, seems even stronger. Founder of I am that Girl Alexis Jones’s remark that adolescents are so «tethered to their devices there actually is no safe space» could be a good example of this.

The same applies to the way some of the sources in the documentary refer, for instance, to Mr Porter’s character as someone who is not skilled enough to deal with the problems that he is faced with: executive producer Brian Yorkey explicitly says, apropos of sexual assaults, «that for victims to talk about it is incredibly hard and takes an incredibly safe space and someone who is very skilled in making it possible for the victims to talk about it. Mr. Porter didn’t have that skill». Alissa Boe’s mention in minute 20 to the «need to build a good support system to be able to heal» seems to insist on this message of hope, and so does child psychiatrist Rebecca Hendrick’s subsequent remark that «(hopefully) people watching this show will feel empowered to be able to go to someone for help» («there’s a million ways that you can find help», Selena Gomez will remind us again later in the documentary).

All these remarks, though, bring the question back to the actual representation in 13RW of this support system and to what extent this can empower the will to ask for help in its viewers. In fact, the recurring tension between hope and the aforesaid sense of inevitability in different passages of the documentary is, possibly –though this will be further explored in the analysis of 13 Reasons Why’s 1st season–, due to the fact that the creators of the show were aware that this aim to transmit hope needed to be explicitly expressed in the documentary because it was not so obvious in the series.

4.2. Comparing the discursive patterns found in Beyond the Reasons and those in 13 Reasons Why’s first season.

The discursive patterns found in the analysis of Beyond the Reasons pointed to a conflict between the intended message of hope recurrently expressed by the creators of the show and a portrait of inevitability that was also mentioned several times in the documentary’s discourse, so these consolidated as the two main starting points of the analysis of 13 Reasons Why’s first season.

The discourse of hope was supported by the also recurrently mentioned notion of help. Different passages of the documentary resorted to the importance of adolescents turning to support networks that could help them, which inevitably asks to examine how they are actually represented in the series. Following some of the leads hinted in Beyond the Reasons, family, friends, and professional support could be considered as the three main axes of support that adolescents are allegedly invited to lean on.

The aforementioned presence of experts in the documentary also suggested that the series’ creators believe that this group is particularly important: Brian Yorkey explicitly said, for instance, apropos of sexual assaults, «that for victims to talk about it is incredibly hard and takes an incredibly safe space and someone who is very skilled in making it possible for the victims to talk about it. Mr. Porter didn’t have that skill». Mr. Porter is, in fact, the first token of the inconsistency between the series and the documentary: the latter highlights the importance of resorting to experts that can lend a hand, but the former chooses not only to use just one that can be identified with this role (a scarce amount, bearing in mind there are four that participate in the documentary) but also to present him as lacking the necessary skills to do his counselling job properly. Such portrayal may lead the audience to see the problems as leaning more on the inevitable side, due to the lack of skilled help, than on the hopeful one, which would probably require more skilful, expert hands.

Mr. Porter’s frequent association to the school’s principal (and, on occasion, with the vice principal) goes further on undermining his role as a reliable source for help, since the directorial staff of the centre are oftentimes presented as mostly managers concerned with the reputation and the economy of the school. This is also notable since the roles of principal Bolan and vice principal Childs may not compute as experts that could be included in the aforesaid support network (though the fact that the show dismisses this possibility is, again, a choice to present them that way), but it can still be considered as undermining the hopeful message that the creators of the show aimed at.

The other big support coming from the adult world in the show, the family, is presented in a less gloomy light, but still far from hopeful. Most of the parents included in the cast of the 13 Reasons Why are at least partly unaware of what really goes on the lives of their sons and daughters, which may not necessarily go against the spirit of starting a conversation noted in Beyond the Reasons as a key discursive axis in the series: spotting the gap between parents and kids could be seen as an attention call by its audiences. A more thorough analysis of the way adult relatives and adolescents are portrayed throughout the series’ first season present a recurring depictive pattern where the former seem not only unaware but at times careless about their kids’ problems (this happens particularly with Hannah and her repeatedly timid attempts to open up to her parents), and the latter feel mostly alone when it comes to taking important decisions -no signs again of the support network here. The case of Clay, who systematically delays conversations with his parents (especially with his mother) can be seen as dismissive and unappealing to parents watching the show, which can in itself go against the goal of starting conversations.

The aesthetic nature of the show, much more visually and sound-wise designed for an adolescent audience, can also be contradicting the conversation goal. Also, from a narrative perspective, the predominant point of view in most passages of the first season is barely an adult’s, as proved by the recurrent use of Hannah’s voice over or the also recurrently leading role of adolescents in most plots of the show. All this, alongside the explanatory gap between Beyond the Reasons, where experts comment on some of the key scenes clarifying certain behaviours, and 13 Reasons Why, where these behaviours are presented without such context, may deter engagement on the adult end of the wished-for conversation.

Friends are possibly the discursive axis where viewers can find more reasons to align with the intended hopeful message, though the outcome of most hopeful turns presented in this section usually keeps leading to a more inevitably destructive end. The original friendship between Hannah, Jessica and Alex is paradigmatic in this respect: it is presented by the protagonist herself as a breath of fresh air but is soon devoured by deceit and disappointment. Friendship as (brief) hope that ends up in disenchantment is so recurring for Hannah that it is difficult to spot one case that does not follow this pattern: even the slight glimpse of hope represented by Robert Wells, who always tries to drag Hannah to the poetry club and never disappoints her, is largely overshadowed by Ryan Shaver’s treason – much more profusely annotated in the show than Wells’ kind attempts.

This disillusioned portrait of friendship is not homogeneous, though Hannah’s predominant role in the show pushes the narrative towards such depiction and it is oftentimes supported by other characters’ disappointments too, like Clay with Sheri or, on a notably higher scale, Jessica with Justin. Generally speaking, though friends provide glimpses of happiness momentarily, the series’ discourse tends to present friendship in a deceitful, disappointing manner. In Beyond the Reasons, Brian Yorkey mentions an example that seems indeed to go against this pattern, the last scene between Clay and Skye that seems to finally break the ice between them; but even there the outcome will end up being far from hopeful, as the second season will only need a couple of episodes to demonstrate.

5. Conclusions

The analysis of Beyond the Reasons has hinted in many ways at an explicitly expressed will on the part of the creators of 13 Reasons Why to transcend entertainment and commit to communicative goals that can be understood as ethically responsible: increasing awareness about uncomfortable realities, starting conversations between the involved parties, and even presenting a message of hope –all of which confirms what was stated in our first hypothesis.

More detailed insights on the discourse of the documentary reveal, however, a tension in the discursive patterns between the intended hopeful message that the creators of the series aim at delivering and a recurrent inevitability trail around all the episodes surrounding its protagonist -and, above all, her suicide. The name itself pre-orients the discourse much more towards a justification of the reasons leading to suicide than to its avoidance, for as much as executive producer Selena Gomez referred to it as something that «should never, ever be an option» –it is actually the protagonist’s option and her reasons are much more well-versed upon than the reasons of the characters who do not choose it.

In fact, the documentary’s dichotomy between a message of hope and another of inevitability is not entirely consonant with the way the events are presented in the actual series: the inevitability end is frequently visited in the show’s first season, whereas there are barely explicit calls for hope. The three main groups –family, friends, and experts– of the support network mentioned in the documentary are debased more often than not, which yet again takes the series discourse closer to the inevitable fate end than to the confidence in finding a way out.

This leads to a partial verification of our second hypothesis; since, even though the discursive pattern of inevitability appear both in the series and its documentary counterpart, the message of hope and the aim at starting conversations have only been effectively detected in the documentary, but not so much in the series. Future researches may shed some light on to what extent this gap perpetuates itself in a pattern in later seasons or, even, in other relevant teen shows.

6. References

American Association of Suicidology (2017). American Association of Suicidology Responds to «13 Reasons Why, American Association of Suicidology, Washington, DC.

Arendt, F.; Scherr, S.; Pasek, J.; Jamieson, P. E.; Romer, D. (2019). Investigating harmful and helpful effects of watching season 2 of 13 Reasons Why: Results of a two-wave U.S. panel survey, Social Science & Medicine, 232, pp. 489–498.

Atarama-Rojas, M. & Requena Zapata, S. (2018). Narrativa Transmedia: Análisis de la Participación de la Audiencia en la Serie 13 Reasons Why para la Aproximación al Tema del Suicidio, Fonseca, Journal of Communication, 17, pp. 193-213.

Ayers, J.W.; Althouse, B.M.; Leas, E.C.; Dredze, M.; Allem, J.-P. (2017). Internet searches for suicide following the release of 13 reasons why, JAMA Internal Medicine, 177, pp. 1527–1529.

Bridge, J. A.; Greenhouse, J.B.; Ruch, D.; Stevens, J.; Ackerman, J.; Sheftall, A. H.; Horowitz, L. M. Kelleher, K. J.; Campo, J. V. (2020). Association Between the Release of Netflix’s 13 Reasons Why and Suicide Rates in the United States: An Interrupted Time Series Analysis, Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59 (2), pp. 236–243.

Cooper Jr., M.T.; Bard, D.; Wallace, R.; Gillaspy, S.; Deleon, S. (2018). Suicide attempt admissions from a single children’s hospital before and after the introduction of Netflix series 13 Reasons Why, Journal of Adolescent Health, 63, pp. 688–693.

Da Rosa, G. S.; Santos Andradesa, G.; Cayeb, A.; Hidalgo, M. P.; Braga de Oliveirab, M. A.; Pilzb, L. K. (2019). Thirteen Reasons Why: The impact of suicide portrayal on adolescents’ mental health, Journal of Psychiatric Research, 108 (2019), pp. 2–6.

Gould, M., Jamieson, P.E., Romer, D. (2003). Media contagion and suicide among the young, American Behavioral Scientist, 46(9), pp. 1269-1284.

Hittner, J. B. (2005). How robust is the Werther effect? A re-examination of the suggestion-imitation model of suicide, Mortality, 10(3), pp. 193–200.

Keen, S. (2006). A theory of narrative empathy, Narrative, 14 (3).

Jones, R. H. (2012). Discourse analysis. A Resource Book for Students. London: Routledge.

Lewis-Beck, M. S.; Bryman, A. E.; Futing Liao, T. (2004). The SAGE Encyclopedia of Social Science Research Methods. London: Sage.

Lyle Bates, G. D. (2019). Narrative Matters: Suicide – Thirteen Reasons Why. Child and Adolescent Mental Health 24, No. 2, 2019, pp. 192–193. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12307

Mar, R. A. & Oatley, K. (2008). The Function of Fiction is the Abstraction and Simulation of Social Experience, Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(3), pp. 173–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00073.x

Mueller, A. S. (2019). Why Thirteen Reasons Why may elicit suicidal ideation in some viewers, but help others, Social Science & Medicine, 232, pp. 499–501.

Niederkrotenthaler, T. & Stack, S. (2017). Media and Suicide. International Perspectives on Research, Theory, and Policy. New York, NY: Transaction Publishers.

Niederkrotenthaler, T., Voracek, M., Herberth, A., Till, B., Strauss, M., Etzersdorfer, E. (2010). The role of media reports in completed and prevented suicide: Werther versus Papageno effects. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 197, pp. 234–243.

Phillips, D. (1974). The influence of suggestion on suicide: Substantive and theoretical implications of the Werther effect. American Sociological Review, 39, pp. 340–354.

Sisask, M.; Värnik, A. (2012). Media Roles in Suicide Prevention: A Systematic Review, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 9, pp. 123-138.

Stack, S. (2005). Suicide in the media: a quantitative review of studies based on nonfictional stories. Suicide Life-Threatening Behavior, 35, pp. 121–133.

Sugg, M. M.; Michael K. D., Stevens, S. E.; Filbind, R.; Weiser, J.; Runkle, J.D. (2019). Crisis text patterns in youth following the release of 13 Reasons Why Season 2 and celebrity suicides: A case study of summer 2018, Preventive Medicine Reports, 16.

Thompson, L.K.; Michael, K.D.; Runkle, J.R.; Sugg, M.M. (2019). Crisis Text Line use following the release of Netflix series 13 Reasons Why Season 1: time series analysis of help-seeking behaviour in youth. Preventive Medicine Reports, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2019.100825

Wartella, E.; Lauricella, A.; Cingel, D. P. (2018). How teens, parents responded to Netflix series «13 Reasons Why», Center for Media and Human Development, Northwestern University. Available at: https://13reasonsresearch.soc.northwestern.edu/netflix_global-report_-final-print.pdf

Notas

1 . Arendt et al. (2019) echo here Hittner’s (2005, p. 199) previous remark that «a basic premise of the Werther effect is that imitative suicides will occur more frequently when there is a high degree of exposure to publicized suicides». Paraphrasing Phillips (1974), Lyle Bates (2019, p. 193) also indicates that the effect «takes its name from the spate of up to 2000 suicides across Europe, which followed the publication and popularity of Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther, published in 1774.»

2 . Arendt et al. (2019, p. 490) also recall previous studies, such as Gould, Jamieson, & Romer’s (2003) or Stack’s (2005) hinting «that suicide depictions may have harmful effects, particularly on those who are already vulnerable to suicide», which may be «consistent with literary and psychological theories of the empathy that stories can elicit (Keen, 2006; Mar and Oatley, 2008)», though «suicidal depictions can also arouse distress in vulnerable viewers, a form of empathy that is likely to lead to avoidance of the story (Keen, 2006)».

4 . In the aforesaid webpage, Netflix indicated that additional material had been created as a response to such request. Most of it, though, merely expanded tools that already existed for season 1: that was the case of the custom intro at the beginning of every season (there was one already in season 1), the increased resources in 13ReasonsWhy.info (the website already existed), or the second part of the aforesaid documentary Beyond the Reasons).